Resources and Tools

Racial Equity Tools

This website is designed to support individuals and groups working to achieve racial justice. This site offers tools, research, tips, curricula and ideas for people who want to increase their own understanding and to help those working toward justice at every level – in systems, organizations, communities and the culture at large. The Racial Equity Tools Glossary is a great place to start.

Additional terms and definitions

The Food System Racial Equity Assessment Tool: A Facilitation Guide

This critical question set and analysis process is designed to support organizations and other groups in prioritizing racial equity when developing plans, programs, or policies related to the food system. While food is certainly the frame for this tool, the questions and process can still be useful in a variety of programming areas.

Centering questions of racial inequities, systems of oppression and privilege, and organizational process and power contributes to stronger programming and more just outcomes for all.

The assessment tool is available on the UW-Madison Extension Learning Store as a free PDF download or to print on demand for $3.50 per copy. Please share this resource widely with colleagues and community partners.

Additional Resources and Tools

- Racial Equity in the Food System Workgroup is a convening of Extension professionals and community stakeholders. Members of this national workgroup are working to connect, learn and collaborate to build racial equity within the food system.

- An Annotated Bibliography on Structural Racism Present in the U.S. Food System, Michigan State University provides current research and outreach on structural racism in the U.S. food system for the food system practitioner, researcher and educator.

- Measuring Racial Equity in the Food System: Established and Suggested Metrics, 2019, This tool offers an expansive list of metrics that U.S. food system practitioners and food movement organizations can use to hold ourselves accountable for progress towards a more equitable food system.

- The University of Michigan course Food Literacy for All is an evening lecture series. The community-academic partnership addresses the challenges and opportunities of diverse food systems.

- Food First provides tools to understand our global food system and to build a local food movement from the ground up. Food First’s analysis and educational resources support communities and social movements fighting for food justice and food sovereignty around the world.

- Draft Principles of Food Justice were developed in 2012 when hundreds of food justice advocates gathered in Minneapolis for the Food + Justice = Democracy conference.

- Journal of Agriculture, Food Systems, and Community Development: Collected Commentaries on Race and Ethnicity includes commentaries on race and ethnicity in food systems work.

- The Center for Environmental Farming Systems Committee on Racial Equity in the Food System (CORE) has a long-term commitment to work internally and collaboratively with community and grassroots groups to address root causes of food system inequities and build collective solutions through the lens of structural racism as an entry point.

- Cooperative Food Empowerment Directive (CoFED) is a queer and transgender people-of-color-led organization that partners with young folks of color to build food and land co-ops.

- The Center for Good Food Purchasing encourages large institutions to adopt an initiative that facilitates shifts in institutional food purchasing toward local food economies, environmental sustainability, valued workforce, animal welfare and nutrition.

- Restaurant Opportunities Centers United is fighting to improve wages and working conditions for the nation’s restaurant workforce.

- The Food Chain Workers Alliance (FCWA) is a Los Angeles-based coalition of worker rights organizations. They advocate for improved wages and working conditions for the people who plant, harvest, process, pack, transport, prepare, serve and sell food.

- La Via Campesina is an international coalition of organizations that defend food sovereignty as a way to promote social justice and worker dignity.

- The mission of Migrant Justice is to strengthen the capacity and power of the farmworker community to collectively organize for economic justice and human rights.

- Farmworker Justice seeks to empower migrant and seasonal farmworkers to achieve fair wages, occupational safety, immigration status, and improved overall living and working conditions.

- 21-Day Racial Equity Habit Building Challenge – Save the date April 5-25, 2021. This challenge is for people of all racial and ethnic backgrounds seeking to deepen their understanding of institutional racism, systems of power and privilege, and contemporary thought on working towards racial equity. The Challenge is made up of brief email prompts and is an opportunity to commit to daily learning and action on understanding and dismantling racism in our lives, work, and personal relationships.

Additional terms and definitions

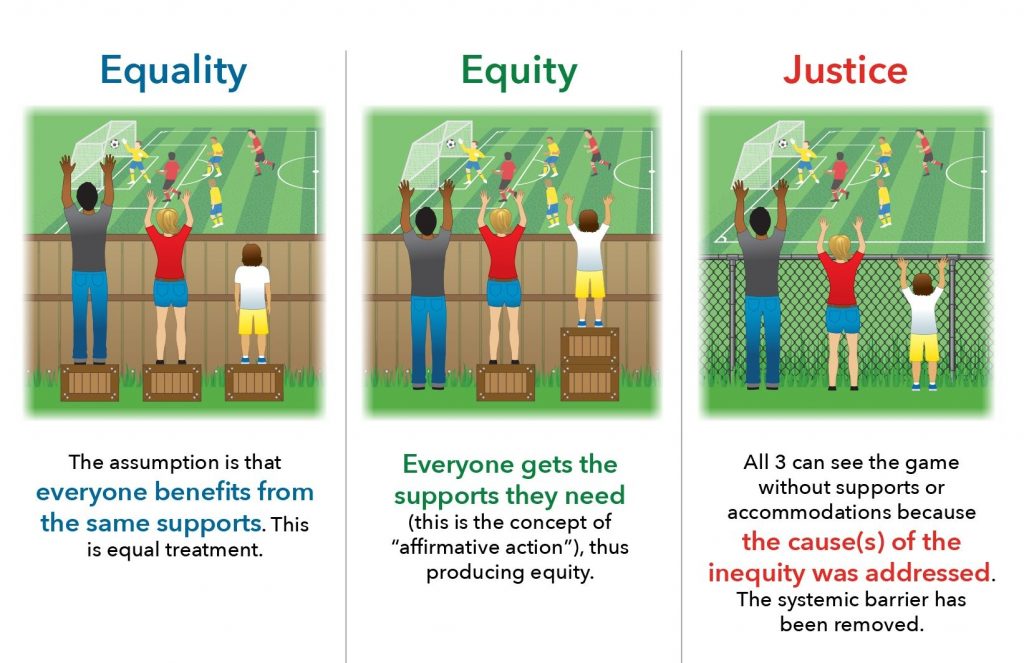

Equality, Equity and Justice

When we provide equal treatment to all, we assume everyone benefits from the same support.

Equity, as in the example of affirmative action, means everyone gets the support they need.

When the cause of inequity is addressed and removed, the result is justice.

Cultural competence and cultural humility

Cultural competence

An examination of one’s own attitude and values, and the acquisition of the values, knowledge, skills and attributes that will allow an individual to work appropriately in cross cultural situations

Denboba, D., Bragdon, J., Epstein, L., Garthright, K., and Goldman, T. (1998). Reducing health disparities through cultural competence. Journal of Health Education, 29(5, Suppl.), 47-53.

Cultural humility

A life-long process of self-reflection, self-critique, continual assessment of power imbalances, and the development of mutually respectful relationships and partnerships

M.Tervalon, J. Murray-Garcia (1998). Cultural humility versus cultural competence: a critical distinction in defining physician training outcomes in multicultural education, Journal of health care for the poor and underserved, Vol. 9, No. 2. (May 1998), pp. 117-125.

The difference between cultural competence and cultural humility

| Cultural competence | Cultural humility | |

| Goals |

|

|

| Values |

|

|

| Shortcomings |

|

|

| Strengths |

|

|

Historical trauma

Historical trauma is the cumulative, multigenerational, collective experience of emotional and psychological injury resulting from cataclysmic events. Events do not just target individuals but a whole collective community. Trauma is held personally and across generations. Even those who have not directly experienced the trauma can feel the effects generations later.

Types of power

Visible power: observable decision-making. Visible power describes the formal rules, structures, authorities, institutions and procedures of political decision-making. It also describes how those in positions of power use such procedures and structures to maintain control.

Hidden power: setting the political agenda. Powerful actors also maintain influence by controlling who gets to the decision-making table and what gets on the agenda. These dynamics operate on many levels, often excluding and devaluing the concerns and representation of less powerful groups.

Invisible power: shaping meaning and what is acceptable. Invisible power shapes the psychological and ideological boundaries of participation. Significant problems and issues are not only kept from the decision-making table, but also from the minds and consciousness of those affected. By influencing how individuals think about their place in the world, this level of power shapes people’s beliefs, sense of self and acceptance of the status quo. Processes of socialisation, culture and ideology perpetuate exclusion and inequality by defining what is normal, acceptable and safe

https://www.participatorymethods.org/method/power

Power analysis

Power analysis: a process that helps organizations and groups to navigate the different dimensions of power, to understand how social issues are shaped and what change could be achieved to improve the lives of the communities those organizations and groups are working with.

https://www.participatorymethods.org/sites/participatorymethods.org/files/Power-A-Practical-Guide-for-Facilitating-Social-Change_0.pdf

Racial capitalism

The process of deriving social or economic value from the racial identity of another person.

Problems with racial capitalism arise when white individuals and predominantly white institutions seek and achieve racial diversity without examining their motives and practices. Striving for numerical diversity, without more, results in awareness of nonwhiteness only in its thinnest form– as a bare marker of difference and a signal of presence. This superficial view of diversity consequently leads white individuals and predominantly white institutions to treat nonwhiteness as a prized commodity rather than as a cherished and personal manifestation of identity.

Nancy Leong, Racial Capitalism, 126 Harvard Law Review 2151-2226 (June, 2013) (374 Footnotes) (Full Document)

Sovereignty

In the United States, federally recognized tribes are considered “domestic nations” with the absolute authority to govern themselves.

Black and African American food sovereignty resources

Black and African American food sovereignty resources Tribal food sovereignty resources

Tribal food sovereignty resources Best Practices for Operating a Food Business out of a Shared Space - 2021 FEED Series

Best Practices for Operating a Food Business out of a Shared Space - 2021 FEED Series COVID-19 WI Food Cart and Food Truck Vendor Resource Guide

COVID-19 WI Food Cart and Food Truck Vendor Resource Guide